By Carissa Patrone Maikuri

In the seven years since I completed my Peace Corps service in the small, beautiful mountain town of Telpaneca, Nicaragua in 2015, I have reflected often about my purpose there and how to reckon with imbalances in power and unearned privilege as a young white American woman working in “development.”

Telpaneca, Nicaragua, during the rainy season

When I left the United States to become a TEFL teacher/trainer at age 23, I thought that I could contribute to something bigger and serve as a catalyst for positive change in an unknown community far away. I was dedicated to remaining open to new experiences, and eager to gain a deeper understanding of knowledge, language, culture, and customs unfamiliar to me.

After spending nearly two years in the community building relationships, working alongside teachers to co-teach English, and leading small projects, I experienced what it would look and feel like to be on the receiving end of international aid. A brigade of about 50 soon-to-be doctors from a well-known health organization were bussed in and out of Telpaneca for three days, performing small-scale surgeries and teeth extractions at the Casa Comunal. At the time — before further reflection — I believe this to be the very first time I had witnessed the (white) savior complex in action.

Counterparts Hilario, Glenda, Noel, and I

One of the Nicaraguan liaisons with the health brigade heard that there was a gringa living in the community, and came to find me at my home one day as I was preparing to go to school to co-teach. They asked if I might be able to interpret for the doctors, for few of them were fluent in Spanish. I agreed to come by later and invited Hilario, one of my counterparts, to join me. Many community members came up to Hilario and me, concerned that, despite their good intentions, the doctors they talked with did not understand them or their needs.

I had often examined my service, comparing what “development” or “aid” looked like based off of my experience as a volunteer and the experience of the fly-in health brigade — assuming that my presence as a white woman in Telpaneca would somehow cause less harm. Spending two years in Telpaneca gave me the privilege of cultivating deep relationships, developing an understanding of the complexities of a close-knit community, and experiencing the ups and downs of life alongside so many amazing people. At the time I hadn’t understood that my existence as a white woman in the community could be disruptive. In comparing those experiences, I decided that I wanted to dedicate my future work to collaborating alongside communities to advance change in a way that is community-centered, sustainable, and long-term so as to challenge the status quo.

I like to see myself as a connecting bridge, a role that reflects my current position as Program Coordinator with Drawdown Lift, a program of Project Drawdown that focuses on the intersections between climate change solutions, poverty alleviation, and human well-being, particularly in rural communities in Africa and South Asia.

Left: An tattered Nicaraguan flag found at the top of Cerro Mogotón, the tallest peak in the country, on the border between Honduras and Nicaragua

Even today, the legacy of colonization perpetuated through systemic inequities and racism continue to amplify the harms of climate change on communities most impacted — even though they have historically contributed, and continue to contribute, the least to climate change. Through the Lift Climate–Poverty Connections report, we have identified 28 climate solutions that have proven benefits for human well-being that can also contribute to poverty alleviation. We are working collectively to not only encourage change in funding climate solutions but also through policy to better support those most vulnerable to and impacted by climate change.

We all have a role to play in addressing climate change, both as individuals and as a part of a larger system. You can embed climate action into your daily life and your work, challenge the status quo, encourage decision-makers and policymakers to make climate-informed decisions, advance people-centered solutions, and reflect on your own experience to figure out how you can best show up in this beautiful world. Collectively, we have a responsibility to take action on climate to ensure that people in all communities can live healthy and prosperous lives on a thriving planet.

—

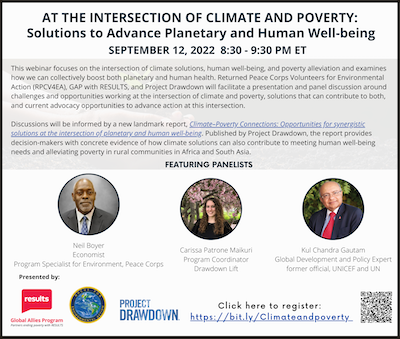

To learn more about the Climate–Poverty Connections report and to tune into a conversation on September 12 on the Intersection of Climate and Poverty with Carissa Patrone Maikuri (Program Coordinator, Drawdown Lift, Project Drawdown), Neil Boyer (Program Specialist for Environment, Peace Corps), and Kul Chandra Gautam (Global Development and Policy Expert and former official, UNICEF/UN), click the link here.

Carissa Patrone Maikuri is the Program Coordinator with Drawdown Lift, a program of Project Drawdown. She was privileged to serve as a TEFL teacher/trainer in Telpaneca, Nicaragua alongside three amazing counterparts from 2013-2015. All views are her own.