Climate Change Book Review

December 2019

In thinking about climate change and the impact it will have on our lives and environment it can sometimes become overwhelming. We wonder: What can I do to stop or lessen the impact of climate change? What is actually happening to the Earth as a result of climate change? Is this article in the media scientifically accurate? How can I explain the situation to my friends? What resources are out there? As such, once a month, the RPCVS for Environmental Action are pleased to offer you reviews of books that span the implications of climate changes from mosses and corals to global politics and technology to personal action.

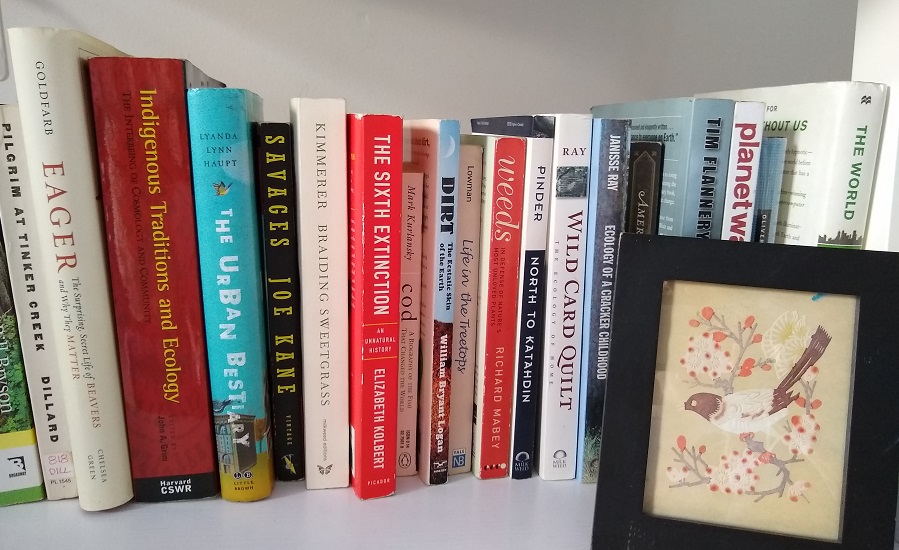

Gathering Mosses: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Growing up, my secret spot was a hillock of moss under cover of a forsythia bush in my backyard. Within shouting distance of the house, it was sheltered from view and a soft cushion for imagining adventures. When I was doing research on the carbon sequestration of dry forests in Bolivia my botanist colleague was cataloguing mosses – getting tiny green leaves all over our office – and causing me to wonder how could so many different species live in such a tiny sample. But beyond admitting its comfortably squishiness and evident diversity, I did not fully appreciate moss.

Gathering Mosses was by no means a guide to identifying mosses but rather a love-song to the bryophyte with descriptions of reproductive techniques and growth habits, line drawings, and a hefty portion of memoir. Kimmerer ties her own perspective as an indigenous botanist and her life experiences to the life cycles of mosses. In 20 or so short essays, she covers the interactions between air and earth, the wide differences in appearances of the family of Dicranum, the use of moss in indigenous cultures, the beauty of bogs, and the (largely human) threats that mosses face.

As someone who has done scientific field research, I especially enjoyed her droll descriptions of settling upon an experimental design. In one memorable passage, she and her field assistant are studying how mosses disperse their clones. They hypothesize that different animals are responsible for carrying the “brood bunches” and then set up experiments to test the idea. Cue the slug derby! The Slugalapolis 500?

Kimmerer’s book flawlessly transitions from the humorous to the profound. She writes, “There is an ancient conversation going on between mosses and rocks, poetry to be sure. About light and shadow and the drift of continents. This is what has been called the dialect of moss on stone - an interface of immensity and minuteness, of past and present, softness and hardness, stillness and vibrancy, yin and yan.” And I for one am excited to join this conversation with listening ears and observant eyes.

Also by Robin Wall Kimmerer:

The publisher Milkweed Editions (where I worked for a hot second) summarized it best: “As a botanist, Robin Wall Kimmerer has been trained to ask questions of nature with the tools of science. As a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, she embraces the notion that plants and animals are our oldest teachers.” In Braiding Sweetgrass, Kimmerer brings the indigenous and scientific ways of knowing together to acknowledge and celebrate the reciprocal relationship that we have with the living world.

If you like Gathering Mosses, try:

Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter by Ben Goldfarb

In Eager, environmental journalist (and my friend) Ben Goldfarb also concentrates on a single forest dweller – the beaver. Goldfarb writes about how the overhunting of beavers has caused widespread changes in the North American landscape. In fact, what we view today as healthy rivers and wetlands are not the species-rich environments that would be present with a flourishing beaver population. Through writing about “Beaver Believers”, the passionate scientists, ranchers, and citizens who work to restore the beaver population, Goldfarb shows how the beaver (and the people who love them) can fight drought, flooding, wildfire, extinction, and the ravages of climate change.

The Trees in My Forest by Bernd Heinrich

Bernd Heinrich expands slightly from Kimmerer’s single non-vascular plant and Goldfarb’s giant rodent to write about the forest as a whole and the relationships of plants, animals, and people. Heinrich uses a lifetime of experience, observation, and teaching, to write lyrical reflections about the forests of the American Northeast. The Trees in My Forest is an exploration of the natural world in scientific and personal terms that highlights the interconnectedness implicit in ecology and our fight against climate change.

Ellen Arnstein was an Environmental Education volunteer in Bolivia from 2007-08. She is now a certified arborist managing a small urban land conservancy’s tree pruning, planting, and landscape work. In her spare time, she volunteers at the Arnold Arboretum in Boston, plays the ukulele poorly, runs slowly, and reads a ridiculous amount of books (mostly about trees). She is also on the Leadership Team of the RPCVs for Environmental Action.

From 2006 until 2008, I lived on one of the coral atolls that make up the Republic of Kiribati, located in the Central Pacific Ocean. I was there to do Health and Community Development work with the United States Peace Corps. During my time in Kiribati, I was amazed by the friendliness and hospitality of the people—although most had few possessions and little money, they welcomed me like a member of their own family and gave me as much as they could offer. I lived with a family that “adopted” me, I made many friends, and I met the woman who I would marry. Although I now live on the other side of the world in the U.S., I am still strongly connected to my family and friends in Kiribati.

From 2006 until 2008, I lived on one of the coral atolls that make up the Republic of Kiribati, located in the Central Pacific Ocean. I was there to do Health and Community Development work with the United States Peace Corps. During my time in Kiribati, I was amazed by the friendliness and hospitality of the people—although most had few possessions and little money, they welcomed me like a member of their own family and gave me as much as they could offer. I lived with a family that “adopted” me, I made many friends, and I met the woman who I would marry. Although I now live on the other side of the world in the U.S., I am still strongly connected to my family and friends in Kiribati.